The Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan is a building where those who, just yesterday, considered themselves distant from art most often stop. Here, on one floor, Van Gogh, Warhol, and a video installation featuring a singing refrigerator peacefully coexist. And in the glass lobby, you might easily encounter someone intently examining a black-and-white stain the size of a towel and asserting, “This is about the war.” The Museum of Modern Art (or MoMA for short) dictates what constitutes current art, how to display it, for whom, and why. This article on i-manhattan.com is an attempt to understand how one cultural institution, since the 1920s, continues to shape perceptions of contemporary culture. And also – why MoMA is constantly changing and with whom it debates.

How the Museum’s Story Began

The history of the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan starts quite unusually: with a women’s club, the Great Depression, and a minor scandal. In 1929, three New York philanthropists – Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, Lillie P. Bliss, and Mary Quinn Sullivan – decided to create a museum that would showcase what “normal museums” did not yet recognize as art. At that time, the American public was mainly captivated by classicism and portraits in gilded frames. And then suddenly – Picasso, Cubism, Surrealism, and the latest European avant-garde school.

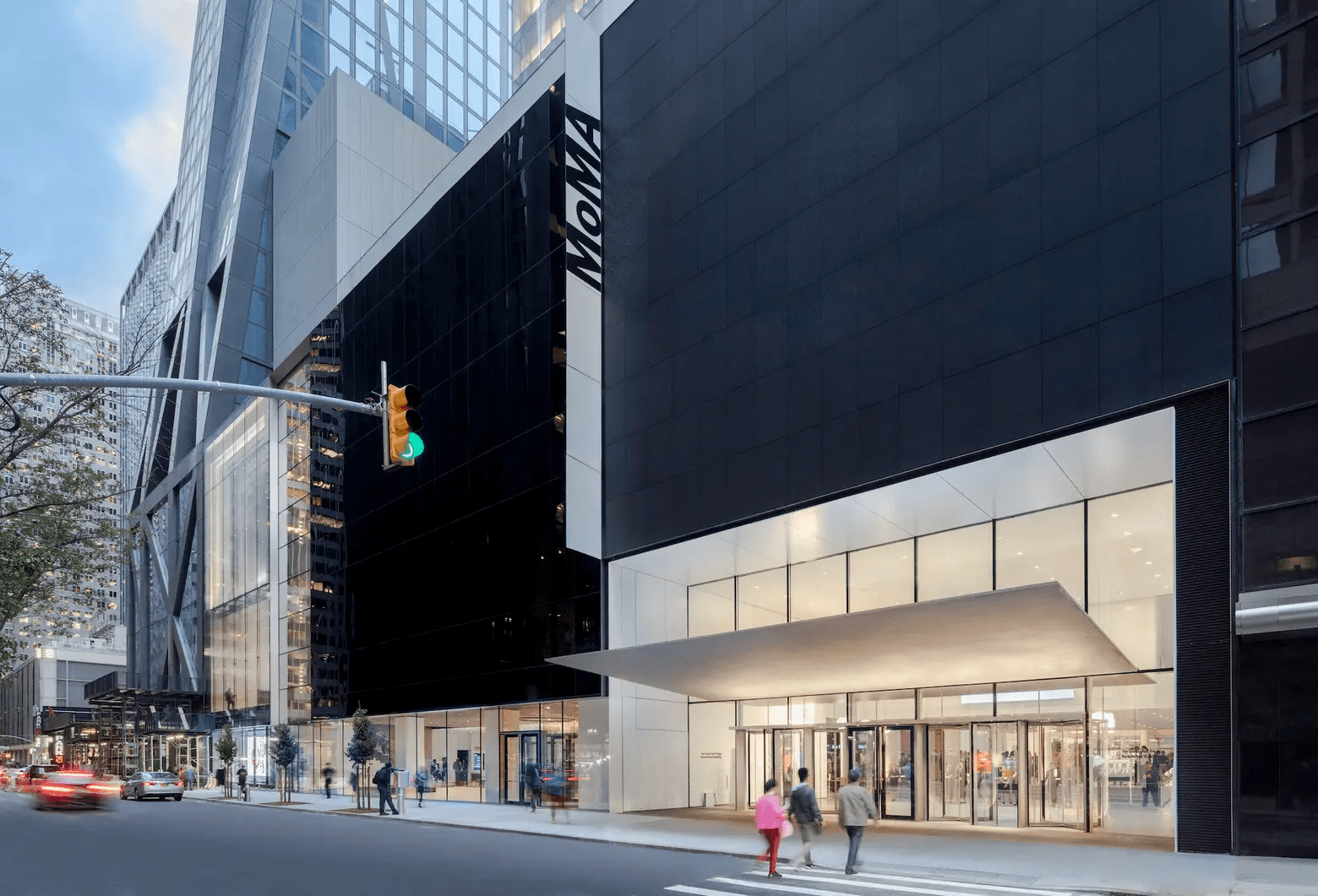

MoMA spent its first years in temporary quarters on Fifth Avenue. But by 1939, it moved into its own building on 53rd Street, where it remains today. Architecturally, the new museum resembled a laboratory – without excessive decor, with large glass facades, and flexible interior space. Its director, the young art historian Alfred H. Barr, Jr., made no secret of his ambitions: MoMA was to become a venue for experimentation, where a painting, a film, and furniture can stand side by side.

This became the first formal “breaking of the mold.” MoMA began to actively intervene in what was considered worthy of attention. It was here that the first large-scale exhibitions of Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, and later – Jackson Pollock took place. That is, even before these names became “classics,” the museum had already integrated them into the cultural field of the USA. And this strongly influenced the American view of art – shifting it from Eurocentric to global.

Incidentally, there is a (not unfounded) theory that MoMA essentially invented the format of the modern art museum: with rotating exhibitions, interactive elements, curatorial concepts, and freedom of form. And that is an achievement.

The MoMA Collection

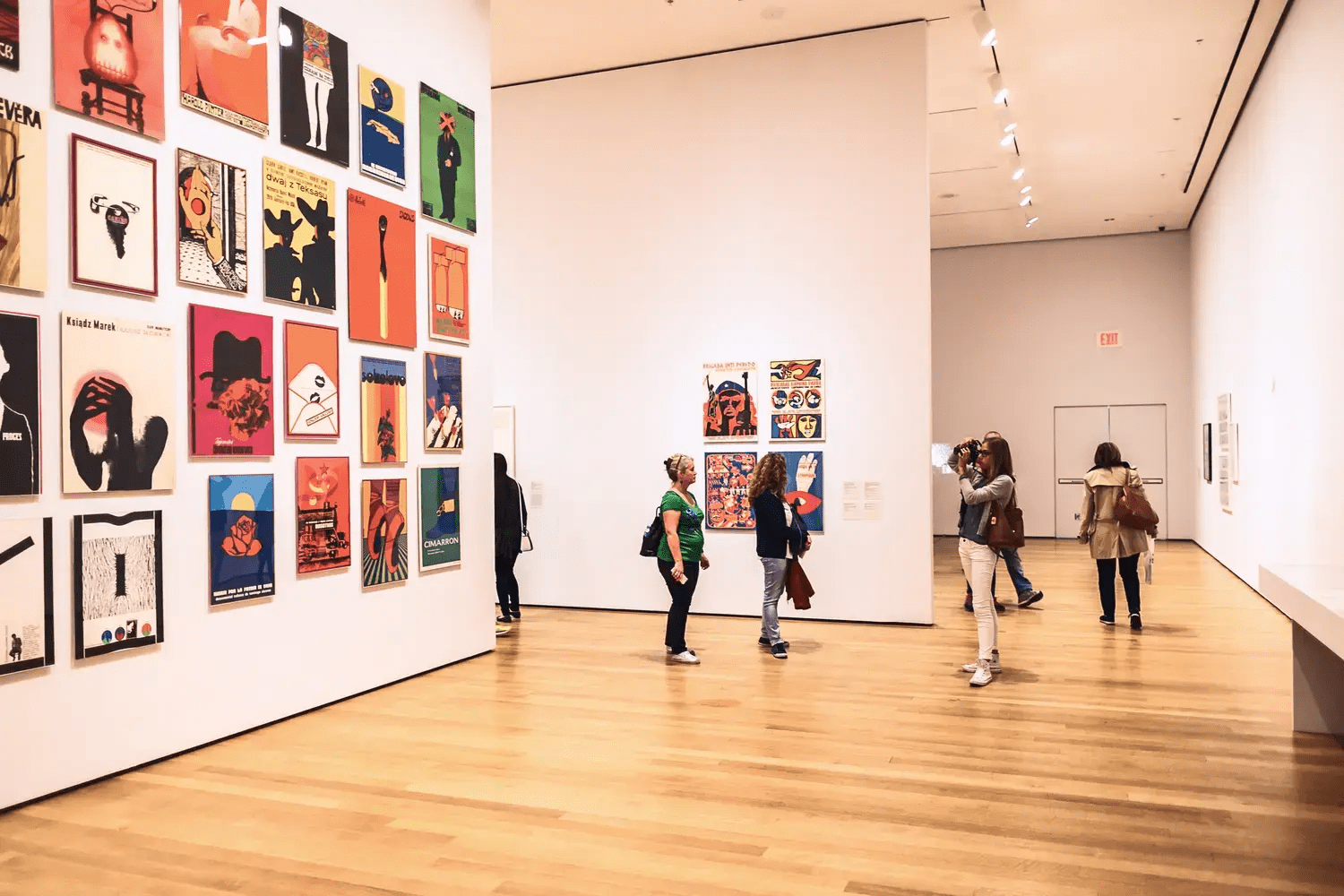

For a long time, MoMA did not have giant halls with half a hundred canvases per meter, but the idea was always present. It was that modern art does not end with painting. As of now, the museum’s collection numbers about 200,000 works – including painting, sculpture, graphics, film, design, architecture, media, and what is difficult to categorize with a single word.

True cultural landmarks are gathered here: from Van Gogh’s “The Starry Night” to Andy Warhol’s legendary Campbell’s Soup can. There are Bauhaus posters, Yoko Ono installations, Walker Evans photographs, and Dan Flavin light objects. But the main thing is that MoMA makes no attempt to “force” works into a rigid chronology or genre. The collection is alive and constantly changing – curators re-examine its structure, shift accents, and add new artists.

Interestingly, a significant part of the holdings is available online. The open digital archive contains over 100,000 objects that can be explored from anywhere in the world. Incidentally, MoMA was one of the first to include industrial design in its collection. They even have the original iPod, the iconic Eames Lounge Chair, early computer fonts, and architectural models of modernist cities. This is how the aesthetic of an era is formed.

And here we note an interesting trend: MoMA is now gradually paying more attention to those it previously overlooked. The collection is increasingly featuring names of artists from Latin America, Africa, and Asia. This shifts the focus from traditional Western art to global narratives. This is a new format for collecting visual culture, where there is no longer a single center.

MoMA as a Cultural and Educational Venue

MoMA always wanted to become something more than a museum – and it seems to have succeeded. A separate educational program has long been operating within its structure: lectures, workshops, children’s classes, online courses, film screenings, and thematic tours. Admission to many of them is free – the issue is not profit, but engaging people who previously considered art “not their cup of tea.”

Interestingly, since the 1930s, the museum has maintained a library specializing purely in modern art. This is one of the largest specialized collections in the world: books, catalogs, magazines, archives, exhibition photographs, and even artists’ personal correspondence. Researchers, critics, and art historians from around the world work here – they are often the ones who prepare exhibitions that later appear in other museums globally.

MoMA is also known for its media archive and cinema. It hosts retrospectives of classics and programs of experimental cinema that won’t be shown even at festivals. There are entire blocks dedicated to animation, video art, and indie cinema from various countries. You can come to watch a short film from the 1970s or a new video from Cameroon – and catch a conversation with the director in the lobby.

Moreover, MoMA has become that museum where even the café makes sense: it’s where ideas are exchanged, and observations are made about who comes here for inspiration or new meanings. This venue has long turned into a place where opinions are formed.

Who the Museum of Modern Art Overlooked and What to Do About It Now

Despite its status as a cult museum, MoMA also has dark spots in its history. The loudest story involved a 1984 protest by a group of female artists holding a banner that read, “Where are the women artists?” The event went down in history as W.A.V.E. – Women Artists Visibility Event. The reason was simple: the museum had predominantly showcased men for years.

Criticism regarding gender representation gradually increased. The center of the exhibitions remained white European and American men who had long become brands. The art of women, artists of color, and representatives of the Global South – remained on the periphery or appeared in separate niche projects.

MoMA did not entirely ignore these accusations but reacted slowly. Only since the 2000s has the museum begun to more actively revise its policy. The new strategy includes expanding the geography of artists, reinterpreting established narratives, and searching for names that, for various reasons, did not make it into the “canon”. The approach has changed – to present the full diversity of artists.

Now MoMA is trying to respond not with declarations, but with actions. For instance, in 2019, after a major renovation, the museum opened with a fundamentally different exhibition: several halls were immediately dedicated to women artists, authors from Africa and Asia, and Latin American art. However, questions remain – and MoMA is still seeking a balance between ideology, audience, and the quality of art.

Why MoMA is Worth Visiting, Even If Art Is “Not Your Thing”

If the word “museum” brings to mind silence, white walls, and microscopic-font labels – MoMA will likely shatter that perception. People don’t walk in circles here with an audio guide; they argue, post stories, take photos of themselves against the backdrop of a “white canvas,” asking, “Is this even normal?”

Modern art provokes thought. One hall throws you into a stupor with color, another with a voice from headphones, a third with a clay model of a skyscraper. Here you might stumble upon an architectural plan for a Detroit neighborhood that was never built, or a photograph of an object that looks like trash but turns out to be an archival document about censorship.

Another plus is the atmosphere. MoMA is literally integrated into the rhythm of Manhattan: on one side – concrete and business centers, on the other – a sculpture garden with a pond and benches where you can linger after viewing. The museum also houses an excellent bookstore, where serious art publications and niche magazines are purchased.

And finally, it is simply a good place to wait out the rain, meet friends, drink coffee with a view of an installation or of yourselves in the mirror. And MoMA is as much an architectural heritage as The Dakota or the Flatiron Building.