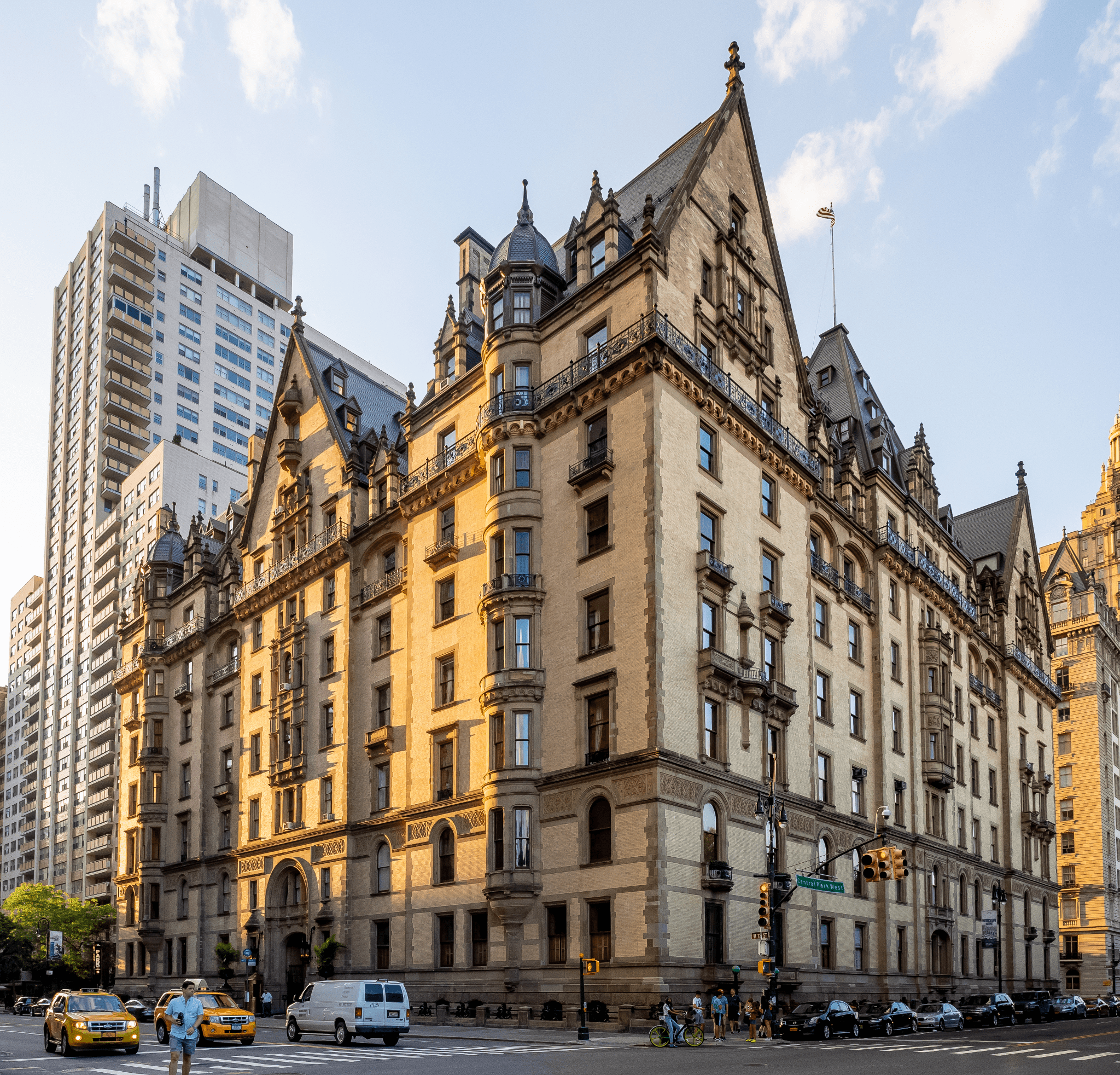

In Manhattan, at the corner of 72nd Street and Central Park West, stands a building with a facade familiar to millions – even those who have never been to New York. The Dakota has long outgrown the “elite housing” category and has accumulated such cultural layers that it sometimes feels as if the spirit of the city resides behind its windows. What made this location iconic for music, cinema, and urban legends – i-manhattan.com investigates.

The Dakota: A Building Ahead of Its Time

In the 1880s, this area was still almost devoid of life – farms, swamps, and a prospect with a view of Central Park, which felt like a suburban landscape at the time. It was here that developer Edward Clark (the same person who founded the Singer company) decided to erect an apartment building for the wealthy. The idea sounded like a joke: what elite would live in an apartment when the city still had plenty of individual houses?

History itself provided the answer. The Dakota became one of the first successful attempts to sell a lifestyle to the American elite. It offered service, space, status, and beneficial neighborly relations. The architect Henry Janeway Hardenbergh (who would later design the Plaza Hotel) created a building that could stand in Paris, Vienna, or Leipzig – with towers, high ceilings, thick walls, and an inner courtyard.

Each apartment was like a separate novel: individual layouts, marble fireplaces, oak floors. Plus – separate elevators for servants, piano rooms, and remote bedrooms. It was seemingly designed for artists and recluses. Thus, The Dakota began to establish a reputation as a home for those who felt stifled by typicality – and who were ready to pay for their autonomy, starting back in the 19th century.

Incidentally, there is a theory that Clark chose the name due to the building’s “remoteness” – suggesting it was almost like the Dakota Territories, somewhere on the edge of the world. As we can see, it worked.

An Arena for the Lives of Artists and Millionaires

Over its 140-year history, The Dakota has become a club with its own rules. To purchase an apartment here, you must pass an interview with the residents’ board. It sometimes seems easier to get into the Venice Biennale.

The fact that the building was intended from the beginning as housing “for its own” also played a role. Actors, conductors, bestseller authors, theater, and television stars lived here. At various times, the doors of “The Dakota” opened for Lauren Bacall, Leonard Bernstein, Judy Garland, and, of course, for John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

Despite this glittering list, the building never turned into a “celebrity museum.” Its residents were those who knew how to maintain distance from the public. And The Dakota has always protected that distance. Stories are known in the press about the board rejecting celebrities whose media biographies seemed “too loud” to them. Among those denied the green light were Madonna, Melanie Griffith, Billy Idol, and even Alex Rodriguez.

In such an environment, a special microclimate forms: where a composer and an Oscar winner might bump into each other in the same entryway, and the general assembly discusses not heating tariffs, but the matter of reinforcing the building’s reputation. This is the style of The Dakota – a miniature Manhattan, with its talents and all the contradictions of its media image.

December 8, 1980: The Day That Changed Everything

Around 10:50 PM on December 8, 1980, John Lennon was returning home with Yoko Ono. Mark David Chapman – a fan who had asked for an autograph earlier that day – was waiting for him in front of The Dakota’s archway. This time, instead of a notebook, he pulled out a gun. Five shots – and musical history suffered a blow from which it took a long time to recover.

Since that evening, The Dakota forever ceased to be merely a privileged address. It became the place where one of the most famous biographies of the 20th century was cut short. A new territory of remembrance appeared in New York: Strawberry Fields – a memorial dedicated to Lennon – was created in Central Park, across from the building’s entrance. People still bring flowers, vinyl records, and notes there, and fans gather there every December 8th.

The Dakota became a symbol of what John Lennon managed to embody: faith in art and the vulnerability of stars, as well as how damaging external obsession can be.

But there is another side. Residents of the building have spent decades trying to live their normal lives – despite the cameras, the tourist pilgrimages, and the fan flash mobs. This is also the paradox of The Dakota: a building that dreamed of being intimate became one of New York’s most public locations.

A Benchmark in Film, Music, and Urban Legends

Outwardly, The Dakota resembles an old European hotel more than a typical New York residential building. Towers, sharp arches, iron balconies – all this creates an atmosphere that directors could not ignore. The most famous cinematic episode is Roman Polanski’s film “Rosemary’s Baby.” The Dakota was used as the building where the film’s events unfold, and after the premiere in 1968, the building permanently secured its reputation as an “ominously aesthetic” location.

This place lives on in culture also through micro-stories – The Dakota is mentioned in songs, novels, and urban legends. It is said that ghosts have been seen here. Rumor has it that Lennon himself spoke of strange phenomena in his apartment. And whispers circulate about hidden rooms, secret passages, and found letters. Part of this could easily be dismissed as New York folklore, if not for the fact that these stories are regularly updated.

In this sense, The Dakota functions as a perfect cultural machine: it inspires new narratives without allowing anyone to definitively ascertain – what is fiction and what is reality. For a city that lives by myths, this is the most valuable quality.

Current Life Behind The Dakota’s Walls

The waiting lists for residents at The Dakota are never empty. But the building itself is in no hurry to let anyone in. A strict selection system is still in place – candidates submit resumes and undergo interviews. Everything is considered: financial status, social history, even how the potential resident behaves in the public eye. All this forms the same closed microcosm from which The Dakota draws its strength. Here is an example.

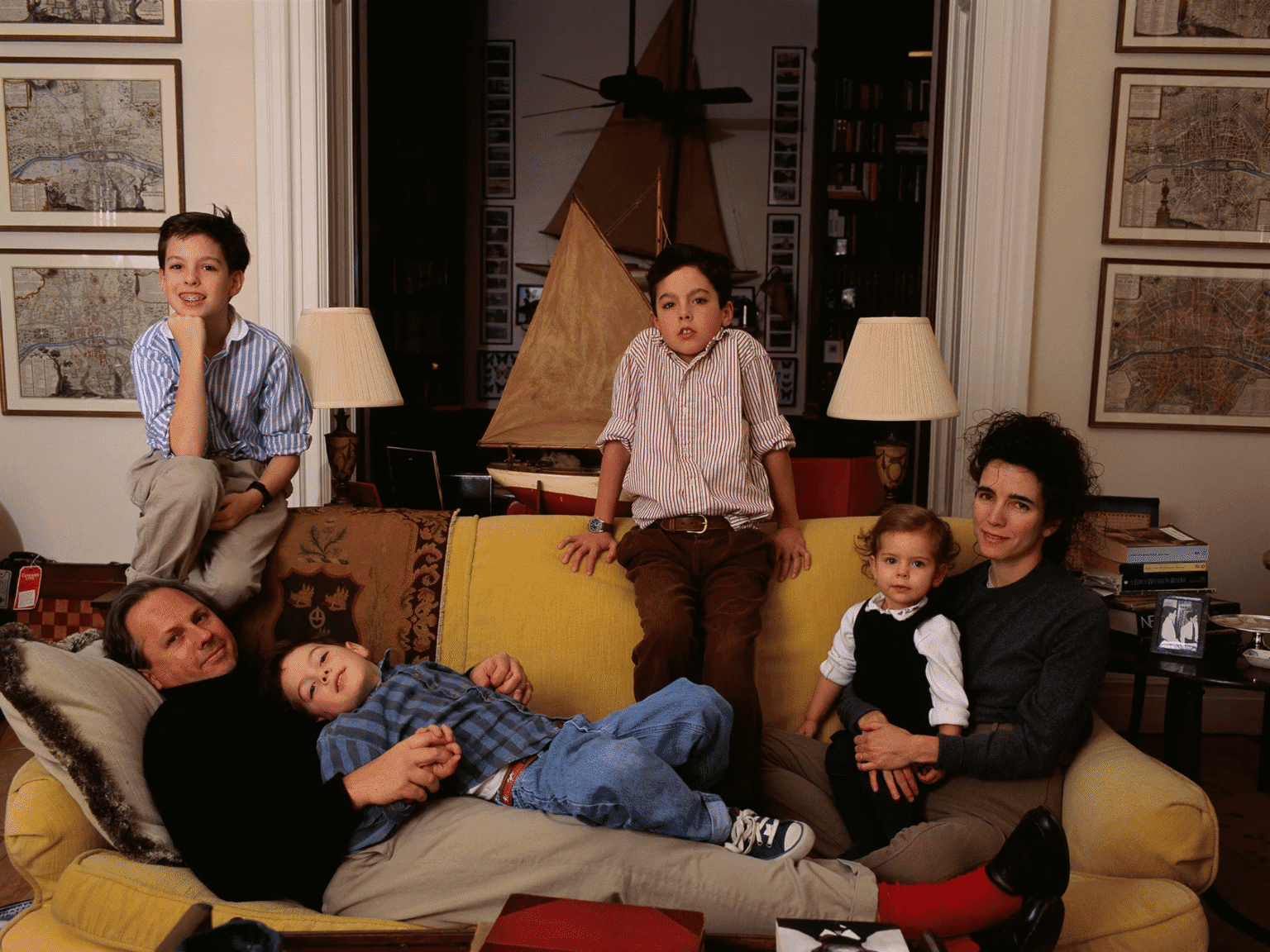

In the living room of filmmaker Alain Pro’s family – a wooden sailboat, maps on the walls, bookshelves reaching the ceiling, and the comfort of “good old New York.” It is like a frame from a film about a director who reads Montaigne on weekends instead of scripts. But behind these walls, while children jump on the couch, residents seriously debate whether to admit Madonna or Antonio Banderas and Melanie Griffith to the building. And they decide to refuse because at “The Dakota,” they are looking for those with whom it will be pleasant to share an elevator.

Apartments in the building are a separate economy. The cost can reach tens of millions of dollars, and even for that money, your candidacy may not be approved. But if you are lucky – you receive an invisible club card: access to privacy, quiet, and unique cultural heritage.

Despite its age, The Dakota looks well-maintained and almost unchanged. This is also its peculiarity – while new towers of glass and steel are being built all around, this building stands as a stubborn witness to old New York. Incidentally, according to local realtors, the trend is this: interest in historical buildings has grown after the pandemic. People are looking for a place with soul and character, and in this regard, The Dakota is top tier.

A Place That Remembers

The Dakota is a cultural memory in stone, where every detail resonates with New York’s history. On one side – a facade behind which hide silence, luxury, and exclusivity. On the other – the shadow of John Lennon, the whisper of fan pilgrimages, and the echo of films that permanently inscribed this building into the global cultural archive.

And although the building tries to live “like everyone else,” it is unlikely to succeed. Because every piece of news about an apartment listed for sale, every old photograph on Reddit, every blog about “ghosts in The Dakota” fuels its reputation.

Let’s look analytically: The Dakota is an interesting example of how a place becomes popular not through PR or branding, but through the convergence of time, place, and personalities. This formula cannot be intentionally replicated. And this is precisely what makes The Dakota unique, particularly for cultural historians and sociologists. Another example of a culturally significant building is the Village Vanguard – a basement where jazz has lived for a long time.