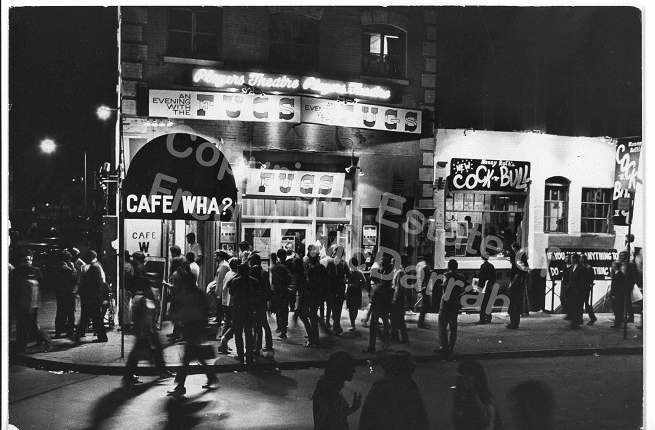

Café Wha? has long become part of New York City folklore. Its basement on MacDougal Street is photographed by tourists, and locals recall it with a smile, even if they have never been there. The i-manhattan.com website will tell you the most important things about this place, separating truth from myth, and analysis from common clichés.

In most texts about this club, everything boils down to clichés such as: “This is where Dylan started, Hendrix played,” “Woody Allen stopped by here.” And that’s seemingly true – but not the whole story. Because behind this legend, a more interesting fact is lost: how this place became a springboard for a generation that went against commerce, conformity, and the mainstream. Who started the process? Is it possible to recreate something similar today, in the world of YouTube and TikTok?

Before the Legend: How and Why Did Café Wha? Emerge?

In 1959, a coffeehouse opened in a former stable in Manhattan – sounding like a bad joke or the beginning of a comic book. But it was run by Manny Roth, a World War II veteran and theatre enthusiast, who clearly understood one thing: New York lacked a stage where “misfits” could talk, sing, or joke – without casting calls, gloss, or three-page contracts.

Roth literally assembled the stage out of wood, laid the floor himself with marble fragments, and left the dark paint on the walls, which was meant to hide cracks but accidentally created the perfect backdrop for performances. The further away from the bright neon lights of Times Square, the more willingly future stars headed there.

The name Wha? – where did it come from? It’s a bit of a joke – an equivalent of the local dialect pronunciation of “What?” as “Wha?”. This wasn’t a café for intellectuals or jazz lovers (like the Village Vanguard), but something slightly cheeky, provocative. Roth wasn’t creating anything revolutionary – he wanted an open platform for those who felt constrained by the standard format. That’s why it featured open mic, a live stage, without posters or selection. A kind of “musical democracy” where a guitar or microphone could end up in the hands of a random teenager. Bob Dylan, a promising young man from Minnesota, was one of them.

At that time, the cafe was more like a laboratory: every night was a new experiment. Listeners sat right up close to the artists and didn’t hold back their reactions. And they paid for it not with a ticket, but with tips. The atmosphere was like an intimate apartment gig in a narrow hallway, only with bigger ambitions. And it worked: because against the backdrop of New York’s refined scene and television sterility of the late 1950s, Café Wha? sounded honest.

The Power Spot for the Unknown: Who and How Started Here

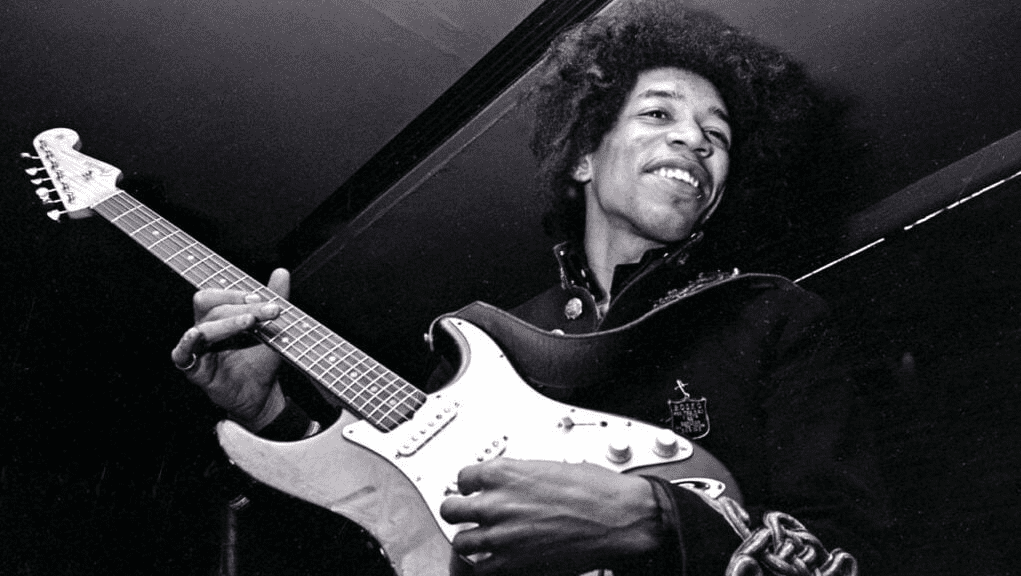

Most legends about Café Wha? sound suspiciously perfect: Dylan walks into the basement, asks for a stage, and something amazing happens. Jimi Hendrix plays five sets a night, and Springsteen performs something in front of live people for the first time. Great drama, but in reality, everything was a bit more chaotic.

Dylan did appear here in January 1961, having just arrived from Minnesota. But he wasn’t a “secret genius,” as is often said. Just another skinny guy with a guitar who stumbled upon a hootenanny – an open mic night where you could sing two or three songs if you managed to squeeze into the schedule. They gave him a few minutes – and that was enough for the audience to remember because he sounded bold, strange, and most importantly – sincere.

Hendrix, by the way, was dragged onto the Café Wha? stage by acquaintances from the crowd. In the mid-1960s, he was still performing as Jimmy James with the band The Blue Flames. The club became a routine stage for him – several sets every night. Technically, it was “survival work,” not a breakthrough. But it was these evenings that polished his style and his habit of playing differently from others. While everyone stuck to blues structures, Hendrix was breaking everything right before the audience’s eyes.

And then there were those who are barely remembered today: stand-up comedians, poetesses, one-night musicians. Often – better than those who became famous. But they were also part of a structure that held together not on labels and producers, but on the principle: “you came – you play.”

But! Café Wha? didn’t produce stars. The venue allowed them to test themselves on a live audience – before the media, TikToks, and promos. This is what made the club valuable and, at the same time, vulnerable: everything relied on people, not on a system.

Café Wha? as a Cultural Model: Not a Show, but a Community

In the mid-20th century, the American scene was either very big or very closed. A showcase for newcomers was either a piano in a club with a dress code or a hallway with a guitar on your knee. Café Wha? attempted a third option: something between a street performance and a full-fledged stage. The venue didn’t take itself too seriously – and that’s why it could afford to do more.

The fact that artists weren’t paid fees (the audience “passed the hat”) created an effect of trust: listeners focused not on consuming content, but on supporting talent. If it didn’t work out – never mind, try again another time. If you hit a chord – maybe someone from the audience will toss you some money for coffee. This atmosphere is almost impossible to recreate today.

Another important point is the genre eclecticism. The programme might feature a folk duo, stand-up about sexism in advertising, jazz improvisation, and a monologue about the Vietnam War, all back-to-back. And it didn’t look like chaos. On the contrary, this is exactly how a new culture was formed – one that didn’t require a single style but demanded honesty.

The audience was also diverse. Columbia University students, poets struggling with addiction, young immigrants, activists writing letters to the “New York Times”… Everyone sat in the cramped hall without clear zones and division into VIP and fan sections.

Decline, Transformation, and Return: How the Club Changed

The romance of the 1960s has one flaw – it scales very poorly. In the case of Café Wha?, this became clear toward the end of the decade. In 1968, Manny Roth sold the club, tired not so much of management as of the continuous struggle with reality. A free stage is good during the establishment phase, but bad when you have to pay for electricity and rent.

The new owners reformatted the space – it was now Feenjon, a venue with Middle Eastern music, dancing, and a different vibe. Still a basement, still MacDougal Street, but without the folk mythology. The club operated like this for almost 20 years. For most New Yorkers at that time, this cafe was a place that vanished in the flow of history.

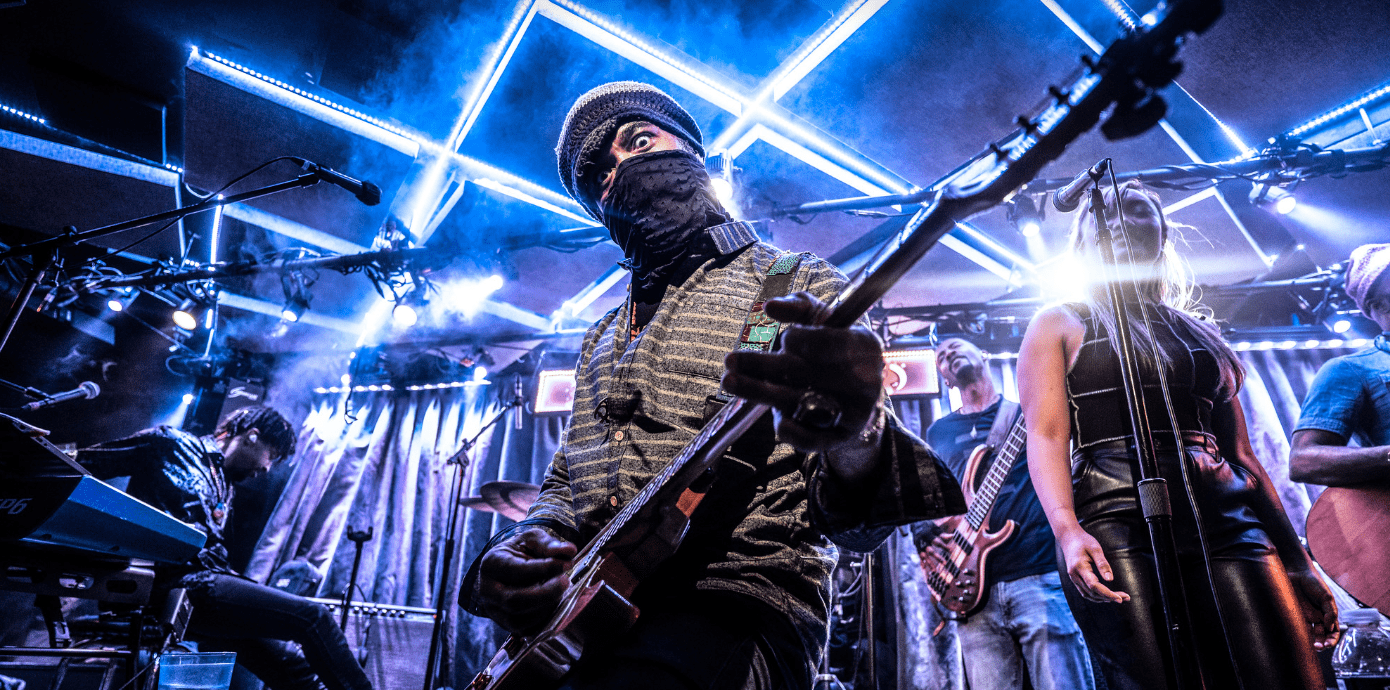

In 1987, the name was brought back. New managers decided: if Dylan and Hendrix played here, it makes sense to create a “backup copy” of the atmosphere. A house band appeared, a repertoire of familiar hits, and posters featuring “legendary stories.” And it worked, but as a nostalgic show.

The irony is that the modern Café Wha? is a quite successful venue that thrives on the tourist flow. It has good musicians, professional sound, and comfortable tables. However, the stage is no longer a place of risk, but a vetted set with a selection of “good old rock” – a kind of Manhattan memorial architecture. For history, this is further proof that even legends become a business if you give them a little time.

Café Wha? as a Cultural Indicator: What Makes a Venue Iconic

Attempts to explain the Café Wha? phenomenon often boil down to the sentimental “art was real back then.” But if everything relied solely on sincerity and intuition, there would be hundreds of such clubs. The problem lies elsewhere: the uniqueness of Café Wha? wasn’t in the romance, but in the combination of three rare things.

- A stage with a low barrier to entry, but high pressure for accountability – the audience was up close and didn’t forgive fakes.

- A cultural ecosystem – a community of artists who interacted, debated, and created a movement.

- A successful historical moment. The early 1960s, the crisis of the consumer model, the human rights movement, and young people searching for a new language.

That is why similar attempts to “revive the atmosphere” usually fail. You can’t artificially summon the spirit of an era. A stage formed only by decorations is an imitation, not a continuation. Community holds more significant value.

And the most popular myth – that Café Wha? was the only hub of counterculture in New York. In fact, no – dozens of clubs operated in Greenwich Village during those years: Gaslight Cafe, Bitter End, Gerde’s Folk City. They all had a similar format and the same artists. The difference is that Café Wha? managed to remain in the collective memory – through its striking name and the unusual history we discussed.

If something similar emerges today, it won’t be a club or a stage, but a digital hybrid. The “open mic” format has already moved to TikTok, but the need for a live, risky, unfiltered presentation has not disappeared. The only question is who will create the platform for it first.