Elizabeth Whelan was an epidemiologist who fought against what she called “junk science.” The prominent scientist founded a national organization that challenged widely accepted notions about food, chemicals and the environment. Whelan passed away on September 11, 2014, in Manahawkin, New Jersey. At the time of her death, she was 70 years old. Learn more at i-manhattan.

She died of complications from sepsis, as reported by her husband, Stephen T. Whelan, in a press interview.

Education of Elizabeth Whelan

Elizabeth M. Murphy was born in Manhattan on December 4, 1943. She earned a bachelor’s degree from the private liberal arts Connecticut College and a master’s degree in public health from the private research institution Yale University. The most prestigious educational institution, Harvard University, she graduated with a master’s degree in natural sciences and a Ph.D.

Photo source: https://msmstudy.com/

Dr. Whelan believed that most studies concerning complex health issues lacked proper scientific grounding. In 1978, she founded her own organization called the American Council on Science and Health (ACSH) to address this evident deficiency.

One of the first scientists to join this initiative was Norman Borlaug, a biologist who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his contribution to the significant increase in cereal crop yields, known as the “Green Revolution.”

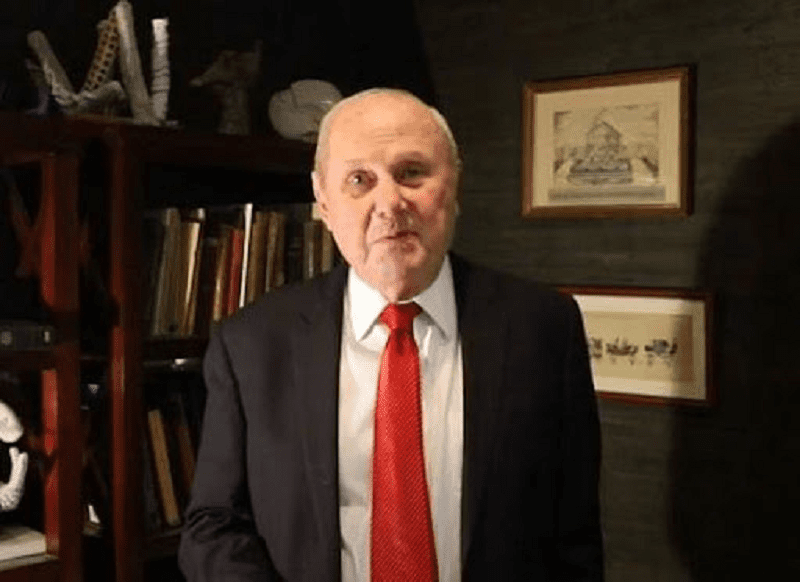

Dr. Whelan previously worked with Dr. Frederick Steven Starr, who founded the Department of Nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. They wrote the book “Panic in the Pantry: Facts About Food, Fads, and Fallacies” in 1975. It stated that many federal food regulations were absurd.

The main idea of the organization founded by Whelan

The main claim of the council was that some chemicals and products were regulated without evidence of their harmfulness. As a result, Dr. Whelan often found herself on the side of the industry, which partially funded her efforts, against consumer and environmental groups and regulatory agencies.

Initially, the council rejected corporate funding, although it accepted money from private foundations. However, by avoiding corporate donations, the founders limited the fundraising capabilities of ACSH without success. Dr. Whelan wrote about this in a comment on the 25th anniversary of the pro-industry human rights organization in 2003.

Thus, the council’s board voted to accept corporate donations without any conditions. According to her, in 2003 she received about 40 percent of her funding from corporations.

Critics argued that corporations donated because the council’s reports often supported industry positions. Dr. Whelan wrote that she was regularly labeled a “stooge of the food industry.”

The organization advocated for various chemical products, including saccharin and other artificial sweeteners, pesticides, growth hormones for milk cows and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). However, it also supported regulation on the sale of firearms and tobacco products, as well as bicycle helmets.

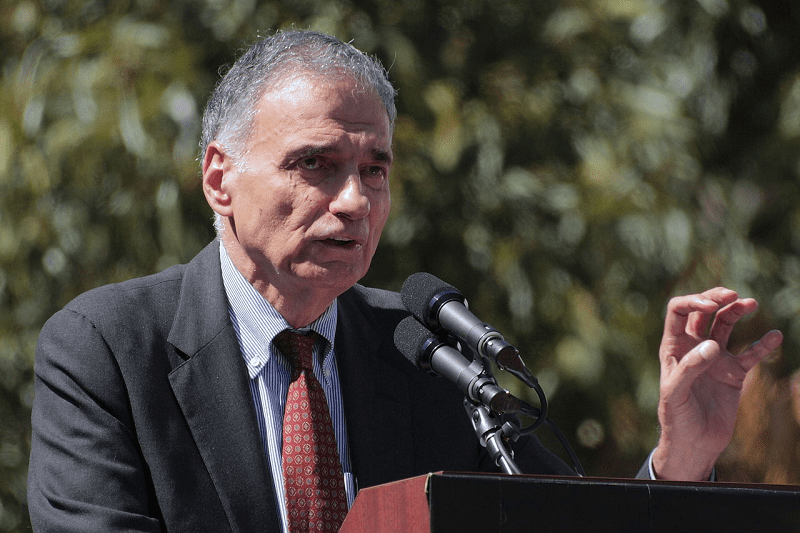

Ralph Nader. Photo source: https://ru.wikipedia.org/

Having the support of over 350 scientists who voluntarily dedicated their time, the Council prepared documents and promoted its views through television appearances and columns by Dr. Whelan and other media outlets. She ignored critics of smokeless tobacco, which in her opinion was far less harmful than traditional tobacco. She also supported the controversial method of drilling oil wells known as hydraulic fracturing or fracking.

The Council also stated that public interest groups led by individuals like attorney and political activist Ralph Nader are preventing people from making personal choices when there is no proof of danger. One such scare tactic was former Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s attempt to limit the sale of large portions of sugary soda in New York City.

Former mayor of New York Michael Bloomberg. Photo source: https://ftime.by/

Consumer and environmental advocates challenge the organization’s conclusions regarding the safety of various products. One self-proclaimed “watchdog” group, the Center for Science in the Public Interest, summarized its view of the Council in the title of a 1982 brochure: “Voodoo Science, Twisted Consumerism.”

But that doesn’t stop the Council. On its website, the organization American Council on Science and Health states that the goal of its critics “is to limit or dismantle many technological achievements that contribute to consumer choice and good health.”

Books by Elizabeth Whelan

After Harvard, Whelan wrote about health for magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar, Glamour and others. In 1974, she published the book “Sex and Sensibility: A New Look at Being a Woman.” It was intended to provide teenagers with simple and understandable information about sex. Two years later, she co-authored the book “Sex and Sensibility: A New Look at Being a Man,” with her father-in-law, Stephen T. Whelan Sr.

In the meantime, she created another book: “Baby?… Maybe: A Guide to Making the Most Fateful Decision of Your Life” (1975). In an interview with The New York Times in 1977, she shared how she decided that her answer would be “yes.” She candidly said that she just panicked because she was about to turn 30.

After the death, Dr. Whelan, who lived in Manhattan, left a husband, a daughter, Christine Moyers, and two grandchildren.

Frederick Starr. Photo source: Muslim.uz.

Her career as a public health lawyer began in 1973 when she became interested in the so-called Delaney Clause, a 1958 amendment to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938. This clause mandated the banning of any chemical substance that could cause cancer in animals or humans. As analytical chemistry advanced, the number of chemicals that could induce cancer in animals was reducing. The law did not take into account actual carcinogenicity.

Banning “at the drop of a rat”

In 1973, Dr. Whelan wrote a controversial article arguing that the development of cancer in one rat out of many due to an almost infinitesimal exposure to a chemical might be irrelevant to human health. Using a frequently cited phrase, she wrote that a certain diet supplement could be banned “at the drop of a rat.”

Overall, she authored 27 books. Some of them criticized the tobacco industry for its lack of transparency, while others prescribed diets.

The title of another book, co-authored with Professor F. Starr in 1983, symbolized Dr. Whelan’s all-consuming passion and at times reckless approach to the matter: “The one-hundred-percent natural, purely organic, cholesterol-free, megavitamin, low-carbohydrate nutrition hoax.”