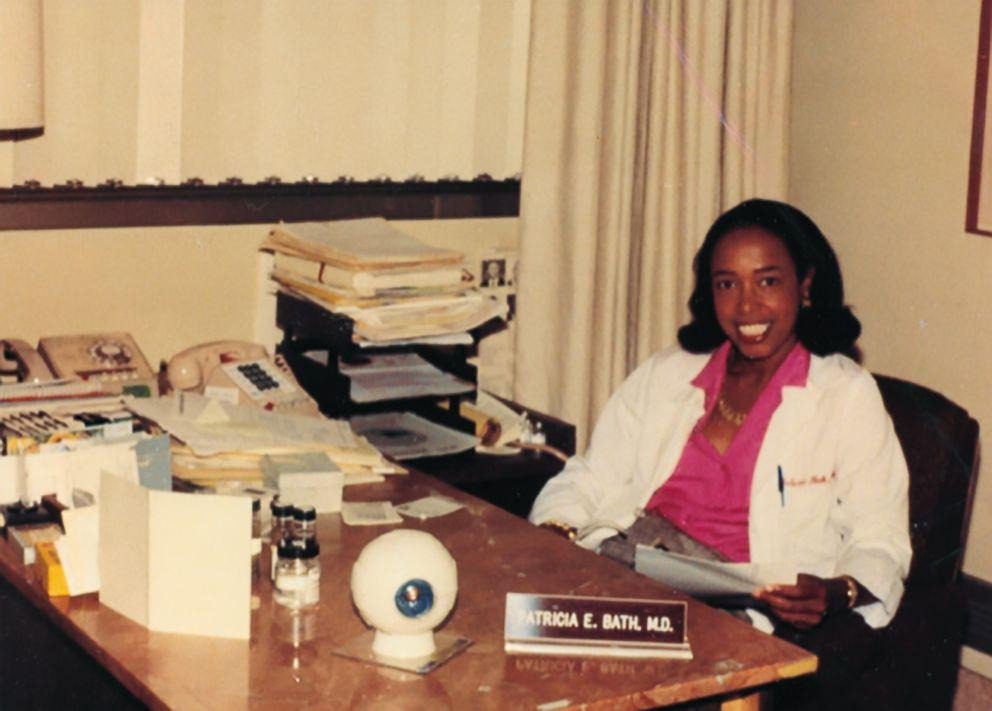

Many inventors who have made enormous contributions to various spheres of human life were born and worked in New York. One of them is Patricia Bath, who was not only a scientist but also a pioneer who broke racial and gender barriers in medicine. At a time when Black women faced systemic discrimination, she became the first African American woman to complete an ophthalmology residency. Many argue that Bath’s work is not only about innovation, but also about ensuring equality in healthcare. We will discuss the life and invention of this great woman in more detail on i-manhattan.com.

Early Life

Patricia Era Bath was born on November 4, 1942, in Harlem, New York. Her father, Rupert Bath, was the first Black motorman in the New York City subway, and her mother, Gladys, was a homemaker and domestic worker who saved money for her children’s education. Patricia was not the only child; she also had a brother named Rupert.

From an early age, the girl showed an interest in and a drive for learning. Her parents encouraged and supported her. Her father, a former Merchant Marine who occasionally wrote a newspaper column, told little Patricia about the wonders of travel and the value of studying new cultures. Her mother fostered her daughter’s interest in science by buying her a chemistry set.

As a result, Patricia diligently pursued science, and at the age of 16, she became one of the few to attend a cancer research seminar sponsored by the National Science Foundation. The program director, Dr. Robert Bernard, was so impressed with Patricia’s discoveries made during the project that he included her findings in his scientific paper. The publicity surrounding her discovery earned Bath a magazine’s Merit Award in 1960.

Pioneer in Ophthalmology

After graduating from high school, Bath enrolled in Hunter College, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in 1964. She then became a student at Harvard University. In 1968, Patricia graduated with honours and soon after received an internship offer at Harlem Hospital. It is important to note that as an African American women entering medicine, Dr. Bath faced significant challenges in a predominantly male field. The scepticism of colleagues and faculty, who were unaccustomed to seeing women, especially women of colour, in such positions, limited her access to mentorship and professional networking. Despite the obstacles, she continued to work persistently.

In 1969, Bath began an ophthalmology fellowship at Columbia University, becoming the first African American woman in this field. Thus, Patricia not only treated people but also conducted research. During her studies, she discovered that Black Americans were twice as likely to suffer from blindness as other patients and eight times more likely to develop glaucoma. Bath’s research led to the development of a community ophthalmology system, which increased the volume of eye care provided to people who could not afford quality treatment. Bath completed her ophthalmology residency at New York University in 1973.

In 1974, Patricia moved to California to work as an assistant professor of surgery at Charles R. Drew University and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). In 1975, she became the first woman to join the faculty of the Jules Stein Eye Institute at UCLA.

In 1976, Bath co-founded the American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness, which established the principle that everyone has a right to sight. By 1983, Bath helped create the ophthalmology residency training program at UCLA-Drew, which she also chaired, becoming the first woman in the country to hold such a position.

The Great Invention and It’s Patenting

In 1981, Bath began working on her most famous invention, the Laser Surgical Device (Laserphaco). Using laser technology, the device, created in 1986, allowed doctors to perform cataract surgery with less pain and greater precision. The probe invented by Bath used laser technology for a minimally invasive and highly effective cataract removal surgery. In 1988, Bath received a patent for her invention, becoming the first African American female doctor to be issued a medical patent not only in America but also in Canada, Japan, and Europe. The Laserphaco probe revolutionised cataract surgery by combining laser fragmentation with ultrasound removal, offering several key advantages:

- Precision. The device created incisions as small as 1 millimetre, allowing for stitch-free procedures and minimising damage to surrounding tissues.

- Reduced Pain. Patients reported significantly less discomfort during and after the operation compared to traditional methods.

- Increased Success Rates. Studies showed that operations performed with the probe had low complication rates and a fast recovery period.

It’s important to note that before Patricia’s invention, cataract surgery involved larger incisions and lengthy recovery times. With her probe, Patricia restored the sight of people who had been blind for over 30 years. This device is used worldwide and has improved the vision of millions of people.

In total, Bath held 5 patents in the U.S., three of which were related to the Laserphaco. In July 2000, the inventor was issued another patent for a method of fragmenting and removing cataracts using pulsed ultrasound energy. Three years later, in April 2003, her analogous patent for combining ultrasound and laser technologies for cataract removal was also approved.

In 1993, Patricia retired from her position at the UCLA Medical Centre and became an honorary member of its medical staff. That same year, she was named a “Howard University Pioneer in Academic Medicine.” Among her numerous achievements, Bath was an active advocate for telemedicine, especially for providing medical services in remote areas.

Personal Life of the Innovator Doctor

In 1972, Patricia gave birth to her daughter, Eraka, fathered by Benny Primm, a doctor who founded some of the first methadone clinics in New York for treating heroin addicts. He was also an advocate for public health policy changes regarding intravenous drug users.

Bath and Primm were married, but the details of their relationship remained private. Patricia’s daughter followed in her mother’s footsteps and became a doctor, earning a bachelor’s degree from the University of California, Berkeley, and graduating from Howard University College of Medicine. Following this, she took a position as an assistant professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at UCLA.

Later Life and Awards

Patricia Bath died on May 30, 2019, in San Francisco from complications related to cancer. She was 76 years old. This great woman’s contribution to medicine was recognized with several awards. In 2001, the American Medical Women’s Association inducted her into the International Women in Medicine Hall of Fame. In May 2018, her alma mater, Hunter College, announced Patricia’s induction into the school’s Hall of Fame. Furthermore, Howard University presented Bath with a Lifetime Achievement Award.

In 2002, Patricia Bath was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. She and her colleague, engineer Marian Croak, became the first Black women to be honored with such a distinction.